Nausicaä. Winter. Joyce.

LOVE WILL BE REVEALED

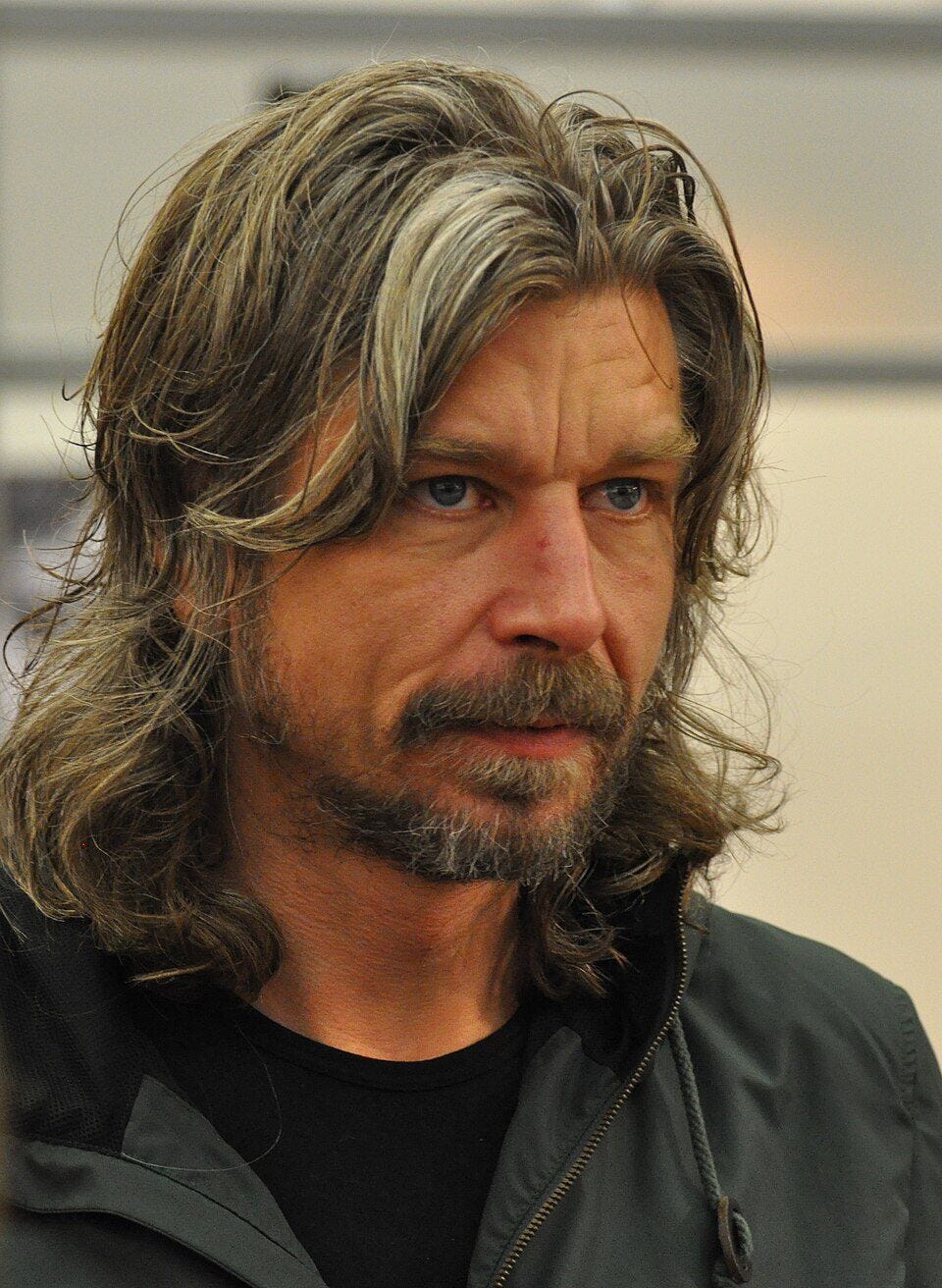

In my substack conversations this week1, Peter C. Baker sent me on a time warp by mentioning Knausgaard in relation to manhood:

Because I have lost all sense of space and time, I think it was twelve years ago now that I saw Knausgaard at the Brooklyn Book Festival. I was volunteering; he was speaking; we had no actual interaction. I can feel myself standing sort of center-left of Knausgaard2, who most likely was seated onstage along with other writers on a panel, but in my mind, he’s solo onstage, standing at a podium and running his hands through his silver mane. There’s no one in the audience but me.

There are variations on this vision, but if you’re here it’s because you’re a reader and like to imagine your own variations. Go to town.

At that tender juncture of my literary life, I had not read any Knausgaard, let alone his Struggle3; all I could comprehend was that I stood witness to an epic mane over a weathered, handsome face. He sort of hunched over, as if he were used to speaking to people much shorter than he was. Maybe there really was a podium? What sort of sexual fantasy involves a podium?

Right now, sitting at my husband’s secondhand desk from his bachelor days in Brooklyn, I could search online for images of Knausgaard and find when, exactly, the silver fox was at the Brooklyn Book Festival, but then I would never finish this essay4. Which must be written, because there is a thread connecting Knausgaard and Cameron Winter and James Joyce and ULYSSES. I suspect that thread is sex, but I am not entirely sure.5 I just want to spend some time thinking about wildly attractive men and one excellent song and an epic that I love. Please join me.6

Nausicaä

I stupidly left post-it notes in just about all my books from New York, and Cologne is a city prone to silverfish. Luckily, they attacked my old Signet Classic Shakespeares first. Repeatedly, actually. I have denuded them of post-its and stuffed them with lavender tea bags, so it was a relief to find that the bugs have not attacked my Homers or Joyces, even though the post-its remain. There’s something about the glue in the Signet Classics, I guess?

Anyway, I was young and unattached when I first annotated the fuck out of The Odyssey, and I found Odysseus quite attractive. He was clever. Men listened to him. Circe wanted to keep him on her island. Who cared about what’s-her-name, weaving the same thing over and over again while the suitors made her life a living hell?7 I don’t think I had much respect for Nausicaa8, either, given that I made notes like “Let’s do laundry!” and '“laundry sounds awesome.” Then again, I also marked “HA!” at this passage from Book 6:

The ball—

the princess suddenly tossed it to a maid

but it missed the girl, it splashed in a deep swirling pool

and they all shouted out—

and that woke great Odysseus.

. . .

Muttering so, great Odysseus crept out of the bushes,

stripping off with his massive hand a leafy branch

from the tangled olive growth to shield his body,

hide his private parts. And out he stalked

as a mountain lion exultant in his power

strides through wind and rain and his eyes blaze

and he charges sheep or oxen or chases wild deer

but his hunger drives him on to go for flocks,

even to raid the best-defended homestead.

Damned if I can’t picture Knausgaard as Odysseus: a storm-and-sea beaten man bewildered by young women playing soccer and beating their laundry against the rocks. (I certainly have no desire to see Ralph Fiennes as Odysseus in The Return, probably because with La Binoche I picture him as a dying man.) That Knausgaardian overwhelm is exactly what’s comical in this scene: it is funny that this character, this “mountain lion” with his “massive hand” hides his “private parts” with a “leafy branch.” I studied Latin, not Greek, but were the Greeks really so modest? Odysseus is caked in salt, half-drowned, starving, and also, somehow, prim? Is his predicament the source of this prudery? He won’t let Nausicaa’s girlfriends bathe him, but insists on doing so himself: “embarrassment” is the very excuse he gives.

But when he’s cleaned up . . . !

Zeus’s daughter Athena made him taller to all eyes,

his build more massive now, and down from his brow

she ran his curls like thick hyacinth clusters

full of blooms. As a master craftsman washes

gold over beaten silver—

. . .

glistening in his glory, breathtaking, yes,

The shame seems gone, but perhaps it was not exactly shame to begin with. Anne Carson explains in Eros the Bittersweet that “Aidōs (‘shamefastness’) is a sort of voltage of decorum discharged between two people approaching one another for the crisis of human contact, an instinctive and mutual sensitivity to the boundary between them” (20). She then references Odysseus later experiencing this emotion as a guest before his hosts, Nausicaa and her family (Od. 8.544). “In erotic contexts,” she continues, “aidōs can demarcate like a third presence, as in a fragment of Sappho that records the overture of a man to a woman . . . ‘I want to say something to you, but aidos prevents me. . . .” (21).

Odysseus is never afraid to speak to Nausicaa and Nausicaa, for her part, is not afraid of him, but hesitation is a live wire running between them, much like the “voltage” Carson describes. The electricity crackles when he stands, filthy, debating whether to “fling his arms around her knees” or to “plead with a winning word”. It appears again when he will not be bathed by her maidens. Finally, it zaps back at him when Nausicaa hesitates to bring him into town “glistening in his glory.” She knows what people will think, because she’s thinking it herself.

Winter, as in Cameron

Winter’s Nausicaä, if you haven’t heard it, has a shuffling step of seduction: a large awkward man approaching with that aidōs of Odysseus. “I am blind,” Winter wails, “and you are ugly / It’s so easy to want you / I want you. I want you. I want you.” Pleading with winning words, he is not. And it is so hot.

To my (elder) millennial ears, Winter’s got a sullen tone I associate with The Strokes, rich New York City boys, Sad Yale boys — maybe these are all the same boys? Boys who are now in their 40s. Boys who might not be your thing, my thing, or . . . even a thing?9

But THIS SONG. I remember reading a review of Dylan’s “Modern Times” in which the writer basically called it a hookup album10. Perhaps Winter’s work falls into that strange landscape of music that is accidentally sexy? Or maybe it is purposefully sexy, much as Tame Impala’s “Feels Like We Only Go Backwards” probably led to the spawning of at least half the tenth graders running around today? Either way, brace yourself for the vivid flashbacks that will accompany “Nausicaä” in ten to fifteen years.

Anyway. I do not have an in-depth analysis of this song. I like the desperation in his wailing little chorus. I like that he says “You can’t smoke here,” because I am old enough to remember smoking in bars being banned. I like that he is “feeling for a pipe to go down,” because I was obsessed with Clarissa Explains It All and the guy friend who always climbed into her window, as well as with basically any romantic comedy that involved boys and windows (SAY ANYTHING). Also, is he even talking about a drain “pipe to go down,” or does he mean . . . ? But most of all, I like the humor in that shuffling beat and the overwhelmed but dogged narrator: he’s addressing his wails to Nausicaä, because we are all epic lovers in our own minds. We all think love will be revealed; we all think that we have washed ashore from the storm and stumbled upon a revelation. It’s sexy because it’s funny and it’s funny because it’s true.

Joyce

In the Nausicaa episode of ULYSSES, we have two people who are feeling seriously sexy, and it is comedic because, like Homer’s Nausicaa and Odysseus, it is not at all funny to them. It’s dead serious.

But it is also comedic because of the situation and use of perspective, both of which begin with Gerty. Somewhere in the vicinity of 22 years old, she sits with two girlfriends who are babysitting annoying twin boy toddlers as she daydreams about the kind of man she will marry. Talking shit (in her own mind) about her girlfriends every time they interrupt her daydreams, Gerty’s perspective is simultaneously heightened and undermined by the style Joyce chooses for the chapter — a romance in a woman’s magazine that constantly interrupts itself with product placement:

Gerty was dressed simply but with the instinctive taste of a votary of Dame Fashion for she felt that there was just a might that he might be out. A neat blouse of electric blue, selftinted by dolly dyes (because it was expected in the Lady’s Pictorial that electric blue would be worn), with a smart vee opening down to the division and kerchief pocket (in which she always kept a piece of cottonwool scented with her favourite perfume because the handkerchief spoiled the sit) and a navy threequarter skirt cut to the stride showed off her slim graceful figure to perfection.

In other words, Joyce writes Gerty so that Gerty objectifies herself. She starts with the outfit she’s worn just in case her ex shows up on the beach, then goes on to catalogue “the lovely reflection which the mirror gave back to her,” her “higharched instep,” “wellturned ankle,” and “shapely limbs.” She mentally accounts for every purchase on her body, down to her “undies” and see-through stockings. Capitalism may have been invented by Dutch Calvinists, but it reaches new heights with the Ladies Pictorial tone of Gerty MacDowell’s Catholic mind.

This is cranked up to eleven when Gerty MacDowell senses Leopold Bloom’s attention and fixates on him:

. . . he who would woo and win Gerty MacDowell must be a man among men. . . .No prince charming is her beau ideal to lay a rare and wondrous love at her feet but rather a manly man with a strong quiet face who had not found his ideal, perhaps his hair slightly flecked with gray, and who would understand, take her in his sheltering arms, strain her to him in all the strength of his deep passionate nature and comfort her with a long long kiss.

Love will be revealed! Gerty sits on a “shelf” along the water while he stands against a rock: the kids throw a ball near him, which he tries to return, but it goes along to Gerty, who exposes a leg to kick it back. She knows he knows she knows he’s watching her from his rock, hand in his pocket, and she knows what his hand is doing. Escalating, she takes off her hat so he can see her hair. One of her bitch friends walks up and interrupts him to ask the time, but when they and the children run off to see fireworks, Gerty gets the full attention of “the gentleman opposite looking.”

To her, Bloom is a man whose “dark eyes and…pale intellectual face” mean that he is a “foreigner,” and she is drawn to “the story of a haunting sorrow . . . written on his face.” Haunting sorrow is indeed on his face: he’s dressed in black for a wake and still suffers from the loss of his son. But Gerty doesn’t know what she doesn’t know. Neither does Bloom, though we are in Gerty’s perspective until after the fireworks, because of course there are fireworks. Something needs to explode.

The erotic tension builds with Gerty’s over-serious, fantastical idea of what, exactly, is happening, interspersed with visions of a Catholic service and the priest who’d told her “not to be troubled because that was only the voice of nature.” She leans back to flash Bloom while he works a hand on himself in his pants. Cue the explosion and “O!”

And because the reader can only see what Bloom and Gerty are willing to see, it’s comedy until it’s tragedy. Trying to sort out his wet shirt, Bloom watches Gerty leave “with a certain quiet dignity characteristic of her but with care and very slowly because . . . . She’s lame! O!” He’s glad he “didn’t know it when she was on show. Hot little devil all the same.” He wonders what she saw in him, reflects on how he “Didn’t let her see me in profile.”

But just as Bloom has had his revelation, Gerty is going to have hers. Earlier, she told herself that “Even if he [Bloom] was a protestant or methodist she could convert him easily if he truly loved her,” but by the end of Joyce’s Nausicaä episode, as the clock goes off in the priest’s house

because she was as quick as anything about a thing like that, was Gerty MacDowell, and she noticed at once that that foreign gentleman that was sitting on the rocks looking was

Cuckoo

Cuckoo

Cuckoo

“Chance.” thinks Bloom. “We’ll never meet again. But it was lovely. Goodbye, dear. Thanks. Made me feel so young.”

That dissonance between what they had not known and what they came to know, I think, shifts the tone entirely. We’re not in the Ladies Home Journal any more, that’s for damn sure. The words Carson uses to summarize Sappho’s fragment 31 apply to Joyce’s Nausicaä: “It is a poem about the lover’s mind in the act of constructing desire for itself.” And that act, for all its humanity, is a tragicomedy. That is the thread through Winter’s song, Homer’s epic, and Joyce’s Ulysses.

We imagine desire into existence, much as one might imagine being the audience of one for a certain “mountain lion exultant in his power” standing at a possibly nonexistent podium in a long-gone Brooklyn, wailing: I want you. I want you. I want you.

Thank you, folks, for being funny and interesting and kind. The world has been too much and our personal world has as well. Markus has been in the north taking care of his parents and coordinating palliative care with hospital visits, while I have been enjoying epic stress at a job I’ll be leaving in two weeks. 2026, baby! wooooooo.

His left, my right. Was he smoking? I think he was smoking. SMOKING HOT.

I first read a chapter from one of his books in a class with Rivka Galchen at Columbia, where I got an MFA in fiction. The chapter was about the humiliating experience of attending a birthday party for a toddler. It was hilarious to me, even though I had only attended a couple baby showers at that point in my life. More recently, I read Book 1. That’s as far as I’ve gotten, though his recent essay in Harper’s has made me want to read more of his work in general.

That said, here he is at the NYPL in 2014 being interviewed by Jeffrey Eugenides.

Write to figure out what you think and/or, as a. natasha joukovsky reminded me, what you want to read.

On the subject of stories told from another POV, I have not yet read Atwood’s Penelopiad, but have dragged it along through at least 5 moves over 15 years, along with what are probably 40 books I do not yet have the itch to read but will not release.

No “ä” in the Fagles translation, because the internet says he wanted to make it more accessible?

Who am I kidding? Look up Igby Goes Down, please. Also, Young James Spader is a total THING, and predates the boys mentioned, but is in no way the Original. See: Newland Archer, Mr. Darcy, etc. Obviously this is another essay.

I am not making this up, but I cannot find the link because that was 20 (!!) years ago. I remembered it because I was SHOCKED, at the time, that people were hooking up to what I considered Elderly Dylan. Modern Times, indeed.

This was fun, Olivia. "What sort of sexual fantasy involves a podium?" indeed. Our collective writerly podium fetish made manifest.

Circe. La Binoche. And these footnotes! Or maybe it is just that I am trying to read KOK’s latest as my first foray and it is a bit MUCH? You are killing me PT Lady.